Traversing CENTCOM: Not for the Faint of Heart

By Neal Simpson

We live in a large, vibrant, colorful world where people of every race, nationality, religion, gender and sexual orientation coexist in peace and harmony. We hold hands, sing “Kumbaya,” and share stories of hope and unity with our neighbors. Rainbows greet us after every rainfall, and the temperature is always a pleasant 68 degrees. And then we wake up.

In the world most of us live in, we may experience a few of these events occasionally at best. This assumes we wake up in our home country of the United States, where it is at least legal to maintain a faith that is different than one’s neighbors and where it is understood that one’s nationality may be different from that of a coworker. Even in the United States, a country quite liberal by global standards, many LGBT Americans still face sexual orientation or gender discrimination, daily battling for acceptance and understanding. Yet our struggles pale in comparison to those faced by LGBT citizens of other nations, especially those within what American service members define as the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) area of operations.

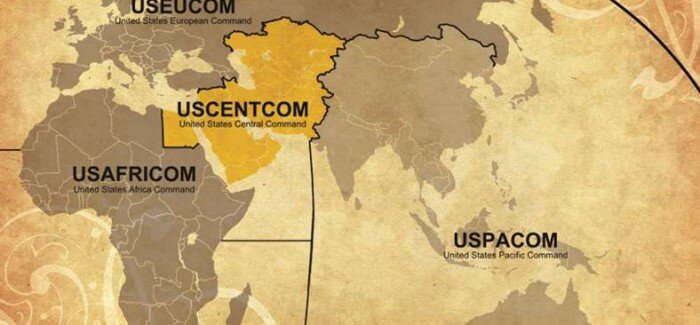

CENTCOM currently covers 20 countries, primarily centered on the Middle East. It ranges from Kazakhstan’s northernmost border with Russia to the coastal waters off the southern tip of Somalia. Egypt is the only country on the African continent included in the area. Given the geographic boundaries, CENTCOM covers the part of the world that most leaders would describe as a hotbed of unrest. This area is home to both the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as numerous geopolitical and military conflicts involving the United States and its allies. For many U.S. service members, a deployment during their service means a deployment to CENTCOM, either in a combat or combat service support role.

CENTCOM currently covers 20 countries, primarily centered on the Middle East. It ranges from Kazakhstan’s northernmost border with Russia to the coastal waters off the southern tip of Somalia. Egypt is the only country on the African continent included in the area. Given the geographic boundaries, CENTCOM covers the part of the world that most leaders would describe as a hotbed of unrest. This area is home to both the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as numerous geopolitical and military conflicts involving the United States and its allies. For many U.S. service members, a deployment during their service means a deployment to CENTCOM, either in a combat or combat service support role.

It is also noteworthy that nearly all nations within CENTCOM maintain either an Islamic government or have a large Islamic population. This concentration often leads to a strict, conservative political and legal system that oppresses many individual freedoms. While this influence does not preclude the ability of a nation to change, it most certainly presents significant challenges to those seeking to implement that change. This brings us to the issue of LGBT freedoms within these countries.

Data on LGBT rights in CENTCOM countries are difficult to obtain; however, the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) maintains a database on these countries, but consider what follows as single-source intelligence. According to ILGA, 12 of the 20 CENTCOM nations have at least one law banning some form of homosexual conduct between consenting adults. Punishments for such activities range from seven years imprisonment to death. The more notably religious conservative nations like Saudi Arabia have the strictest laws (death), while the more westernized nations, such as the former Soviet states of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, have some leniency. These two nations ban sex between males, resulting in prison terms of less than 10 years, but appear to accept relations between consenting women without legal ramifications.

A few nations in CENTCOM legally allow both gay and lesbian relationships, though the extent of acceptance is questionable. These nations include Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Jordan and Bahrain. Although these governments don’t have legal punishment associated with gay and lesbian relationships, it seems clear that the practice of homosexuality (or at least the public display of it) is taboo, with reports of rogue police actions, morality campaigns, and arrests cloaked in the guise of “cultish behavior” and “indecency.” Even the most politically and religiously liberal countries in the region still keep LGBT rights and freedoms at arm’s length, perhaps to avoid the potential spread of Western ideals and the erosion of religious-influenced control over their populations.

The exception in the region is Israel, which is noticeably gay friendly. With its mandatory conscription period for its citizens, Israel allowed gays in its military before America did. The capital, Tel Aviv, has been described as one of the gay-friendliest cities in the world, and gay tourism is booming. This year the nation hosted a gay Pride parade June 8, and gay marriages from other countries are respected despite Israel’s ban on civil marriages domestically. Israel also has laws protecting the LGBT community. However, despite its geographic position, Israel belongs to the U.S. European Command, not CENTCOM.

What does it mean to an American LGBT service member travelling to or being stationed in one of these countries? As a Marine, I travelled to Jordan, Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, and Oman. Though gay, I was closeted at the time to my service, primarily because of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Those reasons notwithstanding, it was never lost on me that in those nations I would be in danger if I appeared to be gay. Even in liberal Bahrain, where I went to clubs and bars with other Marines and Sailors, I was constantly aware of the risks associated with being outed, the possibility of legal or illegal harassment from local authorities. Though the United States now officially recognizes and allows open service for LGB service members, many of the countries in which people serve are significantly less accepting, and the consequences for openness about sexual orientation can be severe.

Go. Learn from other cultures and peoples. Explore the history and the diversity that each of these countries has to offer (within the travel restrictions imposed by the State Department, of course). However, do not confuse your rights to be LGB in the U.S. military with your obligation to uphold the laws and regulations of the host nation. Your actions, behavior, and yes, orientation are best left at home, safe on American soil. For now, take solace in the fact that your service is recognized and appreciated by the country you serve.

The world is becoming more accepting and supportive every day, but for many countries across the globe, specifically in CENTCOM, the progress is slow and the road is long. Good judgment and respect for cultural biases, even those with which you disagree, will keep you safe and allow you to return to the United States to enjoy the freedom you have earned.